The Cracking Story of Mascot Towers

Since 2019, you may have seen mention of Mascot Towers in and out of the [Australian] news ever since its residents were evacuated on 14 June 2019. Often it’s referenced together with Opal Tower in any news related to The Building Commission NSW. However, rather than read about the ongoing drama and heartache experienced by the displaced residents the media seems to preference, you will be hard pressed to find a cohesive narrative as to what actually occurred. This is the story of Mascot Towers.

2008 saw the completion of a residential development comprising two ten storey residential towers, ground floor retail tenancies like grocery stores and coffee shops, all constructed above an underground train station. It was delivered by a builder on behalf of their developer client, the former City of Botany Bay Council. Certifiers acting on behalf of the council issued an occupation certificate (OC) on 1 July 2008. A valid OC is a requirement before occupying or using a new building. It means that the building has been independently checked for safety and compliance, and is in line with approved construction documents.

Three years later in 2011, the body corporate for the Mascot Towers apartment complex recorded cracking observations in their meeting minutes for the first time[1], as well as leaking water observed in the car wash bay. They agreed to appoint a consultant to investigate the defects (at the cost of owner occupiers/investors who pay an annual levy to the body corporate for the maintenance of common property). The consultant undertook their investigation, and being diligent, identified more serious defects, including evidence of structural movement, swimming pool leaks, faulty fire systems, and faulty garden irrigation systems. By 2015 the original builder struck a deal with the body corporate. In the spirit of cooperation, they agreed to repair all the defects identified by the consultant’s report. Furthermore, the building managers accepted $750,000 AUD from the builder to waive any responsibility for ongoing defects.[2] By 2016 the City of Botany Bay Council was amalgamated with the neighbouring City of Rockdale to form Bayside Council.

Eleven years since the construction of Mascot Towers, residents received a letter from the body corporate on 13 June 2019, not only acknowledging temporary props installed inside the car park, but also that they would all have to evacuate by 9pm the next day. Cracking was everywhere: to mortar joints in brickwork piers, to concrete slabs, movement joints, and blockwork perimeter walls in the car park. It was characterised as being “rapid”. Temporary accommodation included a shelter set up at Mascot Town Hall.

A neighbouring apartment complex was completed directly next door, which the residents quickly alleged vibration from its construction caused catastrophic damage to their homes. A reasonable correlation to make (but the causation unable to be proven). Even though the neighbouring developer undertook a condition report of Mascot Towers prior to commencing their own work, which showed cracks existed prior, they reached an out of court settlement. The registered entity used by the original builder to deliver Mascot Towers was liquidated and no longer exists. The building remains unoccupied and condemned, with a deal proposed for a consortium to purchase the apartments from owners at a loss. Rectification is beyond viable. 16 years on its reached a point in its lifecycle that properties aren’t supposed to reach for some 60 years from completion; the end of its economic life, where demolition and redevelopment becomes more likely to yield a greater return than any other option. Not that that will help the owner occupiers or owner investors, now massively in debt with all paths to recourse apparently exhausted.

All this and the exact cause remains a mystery. Perhaps it has been covered up by millions of dollars in out of court settlements between private parties. Building detectives are left only to speculate as to the exact cause, which if known would submit yet another case study to the records, another cautionary tale, and likely further evidence to throw on the pile supporting the case for industry compliance reform. Indeed, both incidents at Opal Tower and Mascot Towers contributed to the eventual reforms to the construction industry in New South Wales (NSW), Australia, with NSW passing the Design and Building Practitioners Act (NSW) in 2020, which included a register for construction professionals and compliance declaration requirements. In May 2022, the NSW Government announced the commissioning of an investigative report into the former Botany Bay Council’s handling of the whole thing. Issued on 21 March 2023 the report focused on process rather than determine any technical causes.[3] Don’t forget, the original builder already paid to dissolve its risk, and then just to be sure, dissolved its company, a likely special purpose vehicle to protect them against this very scenario.

Movement in a building is normal. Buildings move! They are moved by ground conditions and the weather. They move when temperature makes materials expand and contract. And they are prepared to move in concert with a seismic event. And so, they are designed to move. Even settlement is expected following completing construction, where a building’s weight fully settles into its geological foundation over the course of four changing seasons. Hairline cracks, very thin cracks that are no cause for concern, begin to appear at junctions and connections between materials, through mortar joints in brick and blockwork, and in paintwork concealing abutments between plasterboard sheets forming your internal walls or ceilings. These are closed up, sealed, plastered, repainted, and monitored. If the cracks relapse, it may call for a control joint to be installed to tidy things up. Buildings even breath, just as your chest moves up and down when you breath. Movement joints are installed at regular intervals in brick walls and concrete slabs to facilitate these kinds of movements.

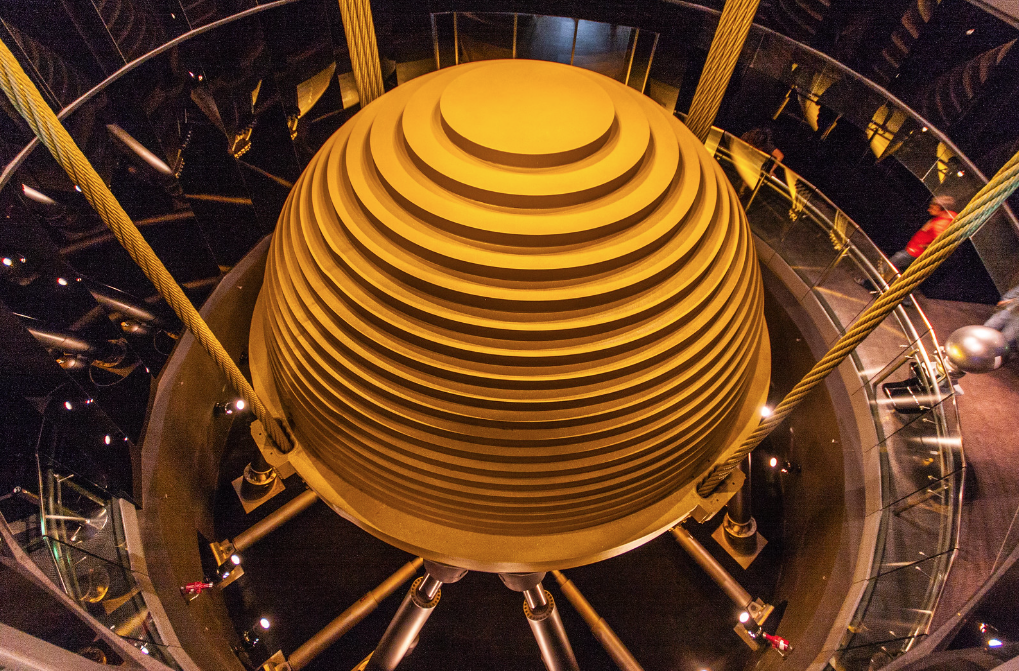

What isn’t normal are sudden cracks, and certainly openings, that indicate too much movement. A rudimentary rule of thumb to consider before becoming too alarmed is if your crack is less than 5mm, get it checked out, sure, but it’s unlikely to be a costly and persisting issue. If the crack you discover is an opening greater than 5mm, perhaps you don’t need to evacuate, but make it a priority to investigate further. Too much movement is the kind of movement where the building is not designed to move that far, this way or that way, and as a consequence, loads are not being distributed correctly risking compromising other elements that were not designed to do certain things. How much movement is too much? Well that depends. Is the property a single story bungalow or a super high rise tower? In 2017 I visited Taipei 101, a 100 story tower located in Taipei, Taiwan. Open to the public was this building’s dampener chamber. Towers this high are subject to heavy wind loads as well as shaking by earthquakes. Subsequently they are designed to move meters horizontally, referred to more commonly as lateral directions.

Even though design allowances can be made to safely accommodate this kind of movement, occupants subject to this movement can experience motion sickness similar to being on a bobbing boat sailing a choppy ocean. To counteract this, high rise towers are equipped with a large dampener. To see one such dampener with my own eyes made me appreciate what an engineering marvel it was. More than three stories high, a massive steel ball is suspended in mid-air in the middle of the tower’s floorplate. As the tower experiences any sort of load causing it to move, the ball counteracts the movement; absorbing it and moving instead of the building.

Not that Mascot Towers ever needed a 600-tonne tuned mass dampener, it’s clear that it did not benefit from any competent engineering forethought whatsoever during design or construction. Transfer beams suddenly found themselves subject to more load than they were designed for, subsequently placing stress on connected components compromising them. When buildings fall down because of this domino effect, it’s called progressive collapse (Hard Rock Hotel 2019, Champlain Towers South 2021). Prevention of these catastrophes really do start at the beginning; practice safe design, use a concept.

The cracks at Mascot Towers clearly gave cause for alarm. Frustratingly, it appears that they were significant enough to be brought to the attention of the building managers just three years after construction. Well before any construction activity occurred next door, well within any typical warranty period, and eightyears before the evacuation. And even though the managers did the right thing by appointing a consultant to investigate, it’s clear that the investigation fell short. That’s not a criticism of the investigating consultant, because it’s entirely possible that the managers didn’t want to spend any more money by expanding the consultant’s scope to include intrusive investigations. Opening up a building is costly and disruptive, and there’s always that fear of the unknown. When you open up, who knows what cost escalation skeletons you’ll find. Suddenly time is at large, that is, works and costs project uncontrollably into the future with no knowable end date in sight. Sadly we’ve watched the possible consequence of this inaction unfold.

We have our observations, now let’s consider our deductions. Even the local MP, Ron Hoening, went on record during a TV interview with an impulsive, perhaps emotionally driven, deduction of his own, “[The neighbouring building] is completed but it has not yet even been occupied and then all of a sudden cracks start developing in the basement of this building …it’s just suspicious when you get that cracking”[4]

Suspicious indeed, but not tested. Simplifying this deduction goes a little like this: A tower next door is constructed, which involves vibrating plant and equipment, and around the same time cracks appear in our building. I deduce that the vibrating plant and equipment resulted in cracking to our building. It’s not difficult to eliminate this deduction, since there’s a record of cracks appearing well before construction activity ever took place next door, andthe neighbouring developer protected themselves by recording the condition of surrounding areas before they got to work. That condition report shows the cracks to Mascot Towers! This is surely enough to bring this deduction under intense scrutiny. To eliminate it completely one would run each of these lines of enquiry to ground by understanding fully the detail of the observed cracks at year three and if they were the same locations as those observed when residents had to evacuate. The same goes for the condition report produced by next door. Yet, when the neighbouring developer was sued for the allegation this deduction is based on, they agreed to an out of court settlement. Moving on.

On 25 June 2019 NSW Deputy Premier, John Barilaro publicly declared a theory of his own (apparently based on geotech reports he had read[5]), that Mascot Towers was sinking due to a drop in the water table, once more attributing this drop to the neighbouring construction work.[6] The sinking the Deputy Premier likely referred to is known as differential settlement. This is where different parts of a building sink at different rates, causing tension to various building elements, eventually compromising the structure allowing part of it to move downward with the moving ground.

So far we have two deductions readily offered by public servants who have no qualms putting on building detective hats of their own. I can offer three more making a total of five hypothesis with the potential to explain our mystery of what caused Mascot Towers to move so much:

- Vibration of plant and equipment from an adjacent construction site cause the building to crack in various areas;

- The construction activity from the adjacent site affected the surrounding water table, causing the building to experience differential settlement;

- Mascot Towers is built above an underground train station. It’s possible that vibrations from transiting trains caused cracks to develop over time, eventually leading to a failure;

- Overall poor workmanship by the builder throughout the property’s construction; and

- The inadequately designed structure neglected to consider the full extent of the site context and geological conditions.

The NSW Building Commissioner, David Chandler OAM, told a Parliamentary inquiry that the engineering design of the Mascot Towers was “poor” and that “the builder didn’t know how to read any construction plans”.[7]

As always, the conclusion could feature a combination of more than one deduction, and still deductions we have yet to dream up, or reveal themselves during our investigation. All anyone can do is begin the process of eliminating each of these one at a time until we arrive at the deduction that is the most difficult to disprove. That might be our conclusion. Only when you can prove it using evidence is it absolutely your conclusion.

All too often I read professional consultant reports that simply fall short in both their communication of technical matters in plain, clear language, and more importantly, are too quick to draw conclusions without evidencing due process, ultimately providing ‘bad advice’. ODEC (Observation, Deduction, Elimination, Conclusion) is the one thing I’d like all of those professionals to take away from The Building Detective, and some level of comfort that one does not need to absolutely reach a conclusion, for even the most intense and detailed of investigative enquiries show that this is often not possible, only a consideration of a probable conclusion.

Interpreting cracks is an art in itself. Deductions can be made simply by understanding crack width, direction and context. In fact, there are whole books written on the subject to assist practitioners to develop their interpretation craft. The Practical Guide to Diagnosing Structural Movement In Buildings[8] by Malcolm Holland MRICS is an excellent resource, outlining first principals with clarity ahead of demonstrating how to apply them using a variety of examples. Malcolm suggests a user of his guide would be able to diagnose the majority of cracks within just a few minutes. CISRO also provides a white paper written for homeowners that provides a good, basic grounding in building movement and cracking[9].

CJLM

This is an excerpt from The Building Detective: Uncover building mysteries and solve them like a sleuth, a new book for problem solvers.

[1] “Not Us Says Aland, as Mascot Towers Crack Concerns Investigated in 2011.” Urban.com.au, 7 Dec. 2020, www.urban.com.au/news/not-us-says-aland-as-mascot-towers-crack-concerns-investigated-in-2011. Accessed 13 June 2024.

[2] Stephens, Jodie. “Mascot Towers: Twist in Case of Cracking Apartment Block.” 7NEWS, 27 June 2019, 7news.com.au/news/sydney/mascot-towers-investigation-continues-c-187563. Accessed 13 June 2024.

[3] “Investigation Report – Mascot Towers Development.” McCullough Robertson Lawyers, 21 Mar. 2023, https://www.parliament.nsw.gov.au/tp/files/186318/Mascot%20Towers%20Investigation%20-%20Report.pdf

[4] Henriques-Gomes, Luke. “Mascot Towers Residents in Limbo as Berejiklian Promises Action.” The Guardian, 16 June 2019, www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2019/jun/16/mascot-tower-residents-in-limbo-as-berejiklian-promises-action. Accessed 13 June 2024.

[5] “Legislative Assembly Hansard – 18 June 2019.” Nsw.gov.au, Parliament of New South Wales, 2019, www.parliament.nsw.gov.au/Hansard/Pages/HansardResult.aspx#/docid/HANSARD-1323879322-105975/link/97. Accessed 13 June 2024.

[6] June 2019, Leith van OnselenThursday 27. “Developers Blame Each Other for Cracking Slum Towers.” MacroBusiness, 27 June 2019, www.macrobusiness.com.au/2019/06/developers-blame-cracking-slum-towers/. Accessed 13 June 2024.

[7] Santoreneos, Anastasia. “Mascot Towers Is Most “Poorly Built” Building Ever Seen.” Yahoo Finance, 21 Aug. 2019, au.finance.yahoo.com/news/mascot-towers-is-most-poorly-built-building-ever-seen-004041672.html. Accessed 13 June 2024.

[8] Holland, Malcolm. Practical Guide to Diagnosing Structural Movement in Buildings. Chichester, West Sussex ; Ames, Iowa, Wiley-Blackwell, 2012.

[9] “Foundation Maintenance and Footing Performance: A Homeowner’s Guide.” CSIRO, CSIRO Publishing, 2003.